Sneak preview of one the songs that musicians and lyricists are busy working on for the Song of Contagion show, which will run June 13-17, 2017 at the fabulous Wilton’s Music Hall: the Dengue Merengue. We’re using the contrast between dengue and zika to demonstrate how important media coverage can be in determining how much attention and funding a disease gets.

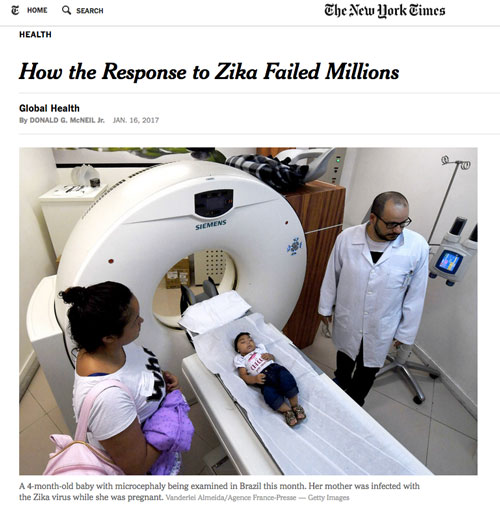

The New York Times this week ran a long story titled How the Response to Zika Failed Millions. Though scientists get a mixed-to-bad scorecard, the press was highly praised.

“In Brazil, the press was the first to sense that something was going on,” said Dr. Karin Nielsen, a pediatrician at the David Geffen Medical School at the University of California, Los Angeles, who also works in Rio. “It was pushing it even before the medical specialists were.”

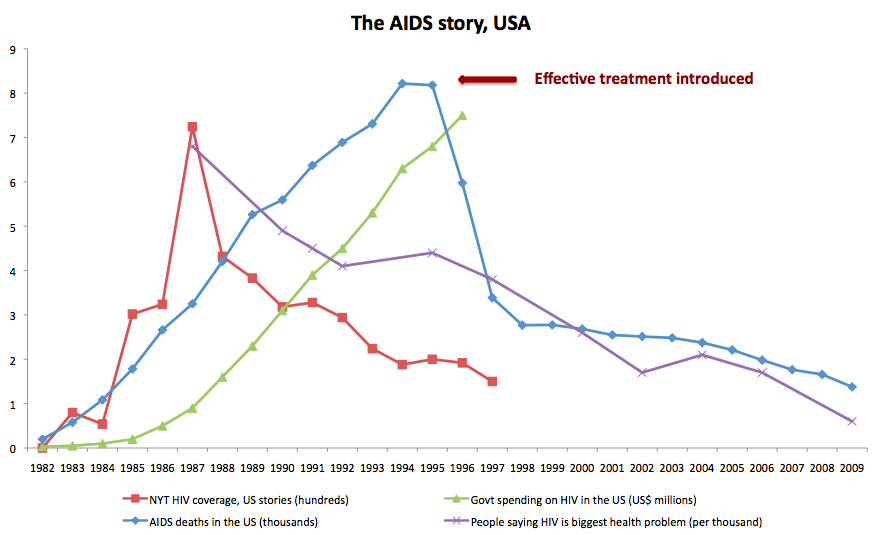

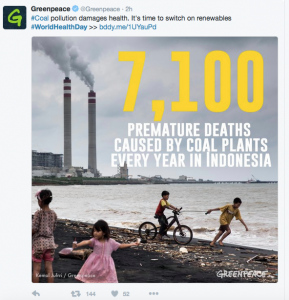

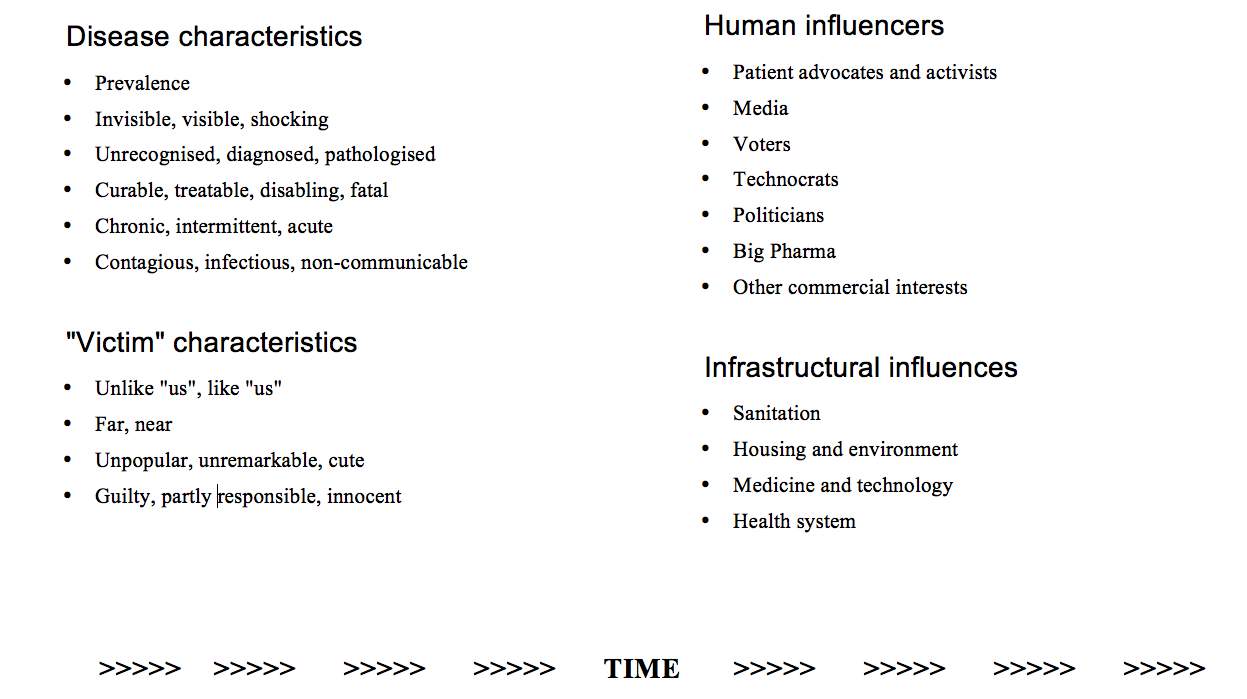

Certainly the press is excited about Zika. In the last year,the New York Times alone has written 1,062 stories mentioning Zika. So here’s my question: why does the press not get excited about dengue? The NYT ran just 173 stories mentioning dengue in the last year, and if you sort them by highest relevance, 14 out of the top 20 have headlines that are about Zika, not dengue. And yet both pathogens are spread by the the same mosquito in largely the same areas. Dengue has been around for ever and is getting worse, debilitating around 96 million people every year and sending about half million of them to hospital. Around 13,000 of those will die. Zika has also been around a while, and it doesn’t seem to kill anyone much, and was thought to do little harm. Recently, though, infection in pregnancy has been associated with some 2,311 cases of microcephaly. That’s pin-head babies, and they make for great newspaper fodder. I’ve no doubt that sounds callous, but it’s an indication of the extent to which photo-ops lead news coverage in today’s screen-obsessed world. The Time’s Zika scorecard story managed to include THREE baby-and-parent photos (and one pic of a mosquito-fogger).

It’s also a perfect illustration of two of the other parameters that affect the importance we give to different diseases. One is what in Song of Contagion we’ve been calling the “cuddly-to-icky” spectrum. Deformed babies and their parents quite rightly excite sympathy in people worldwide; that makes it easier to put them on the front page (and to fund) than less endearing “victims”. Dengue affects people of all ages, including kids, but there’s nothing particularly eye-catching about a patient with dengue shock syndrome.

The other parameter Zika illustrates is the “near-to-far” spectrum. Because Zika came to notice in Brazil, in the Americas and just before the Olympics, it seemed much “nearer” to decision-makers in the United States (and journalists at the New York Times) than many other neglected tropical diseases. And with the Olympics planned, people from lots of other countries would draw near to the virus, too. Of course that’s also true of dengue, but without the shock visuals and the hook of an “emerging” epidemic that Zika provides, physical proximity counted for less. Some parameters trump others, in health as in music.

Another aspect of the Times story reflects something I’ve found recently in my research on scientific collaborations. Investigators in low and middle income countries get really cross when researchers from rich countries treat them as second class citizens.

Dr. Ernesto T. A. Marques Jr., an infectious disease specialist at the University of Pittsburgh and at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation in Brazil, said Brazilian scientists felt let down when they looked for outside help — at first from European donors and health agencies.

“The local researchers’ role was mainly to collect samples,” Dr. Marques said bitterly.

The C.D.C.’s initial reluctance to accept Brazilian scientists’ work also slowed the international response, said Dr. Peter J. Hotez, the dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine.

Even when the Brazilians found Zika virus in two women’s amniotic fluid and in the brain of a microcephalic fetus, “The C.D.C. would not accept it until they had done it themselves,” he said.

While racism is not the exactly right word for this sort of inequity, it has the right flavour. In journalism we’d call it “big-footing.” Local journalists toil away for years telling the story of some forgotten place, and then come the revolution, the tsunami or the World Cup, they get “big-footed” by crusty correspondents — usually white men based somewhere much more comfortable — who don’t speak the language or have any useful contacts but who come in to report the big story, snatching all the glory. One day we’ll learn in science as we are gradually learning in reporting that people with deep knowledge of local cultures, politics and ways of communicating are central to great research. I guess this is what Tony, in his musical discipline, calls “authenticity”. It seems creative work in both art and science depends on it.

Facebook Event page

Facebook Event page

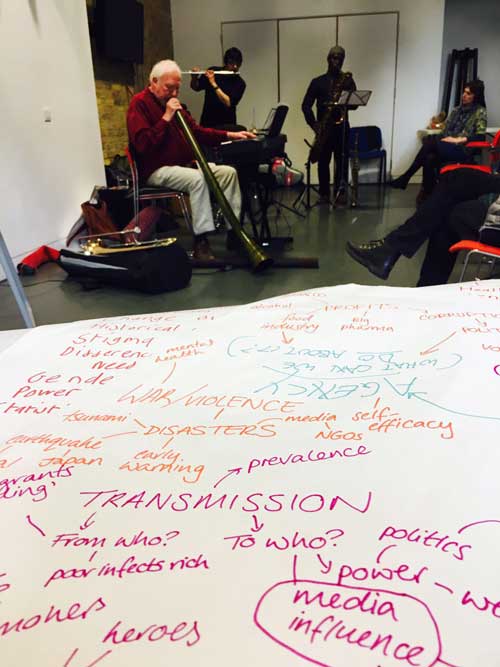

It continued to develop the ideas explored by acoustic instruments in the first workshop, developing and applying the musical parameters through digital means and music technology.

It continued to develop the ideas explored by acoustic instruments in the first workshop, developing and applying the musical parameters through digital means and music technology.