“Turn the corner into Cable Street – a sharp breeze from the river catches you, sometimes the scent of the sea…the street remembers”

So begins Song of Contagion, in the atmospheric setting of a classic Victorian music hall, taking you to the very heart of East London, where cholera raged 150 years ago. The cause unknown, wild theories abound, but eventually the problem is solved: fresh water and an effective sewage system are the answer. Meanwhile Indian voices and instruments describe an equally virulent epidemic gripping Kolkata, in West Bengal; but no such steps are taken there, and thousands continue to die from the disease.

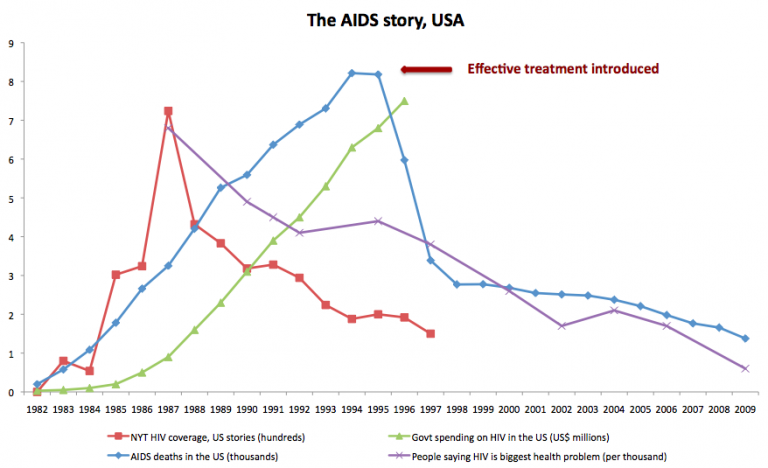

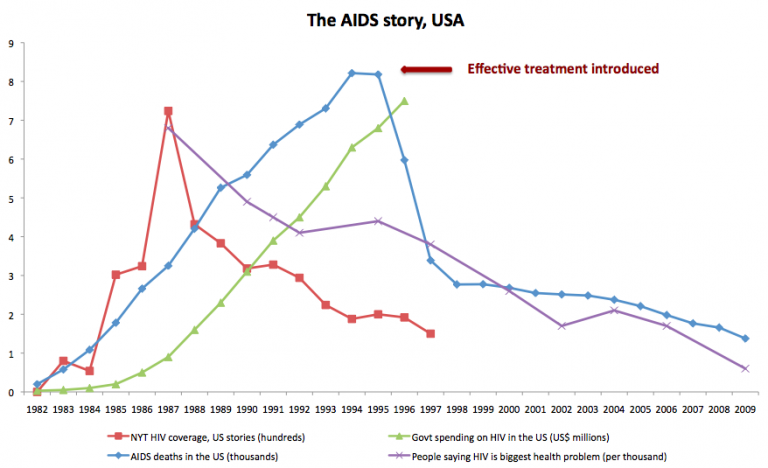

If only all diseases were so simply eradicated. Take the story of HIV/AIDS, told here in a piece I developed from one of the original music workshops described here, using this graph:

GUO musicians animate the lines on this graph, projected behind them. Strings buzz away over drums and bass – the activism of mainly gay men; saxophones portray growing public awareness and media attention, and trombones the initially reluctant government funding for treatment, while a menacing bass drum marks the ever-increasing death rate. Then the trumpets announce a treatment has been found – an expensive one, but the drum beats fade.

Meanwhile, millions of families living with the disease in Africa can’t all be treated until medication is cheaper. Against an African rhythm now, the strings, saxophones and trombones again get to work and the trumpets mellow as the price falls. In some parts of the world, the disease is now being treated, thanks to public awareness and action, but there is still much to be done; as the choir warns us, “easy to turn our backs now – but silence is consent”.

Often only when the media take up the cause is a disease taken seriously; but they are capricious, and need a story – preferably a sensational one…

A mosquito begins to dance over a lilting rhythm from central Africa, where dengue fever is endemic and has been killing tens of thousands for years. However “it’s not going to play if it’s too far away – get lost, I’ve got papers to sell!” is a newspaper editor’s cynical response. Next, with soca and steel pans, she spreads the disease to the Caribbean, but “if the rum is still flowing and tourists keep going, where’s the drama?” the editor says.

Trying a different tack, she sambas off to Brazil, where “…Zika may spoil the Olympics: there’s babies being born with small heads” – “now you’re talking!” the editor said. The mosquito dances off to an exuberant big-band number featuring drums and percussion from all over Africa, the Caribbean and Latin-America.

Now the sound of a heart beat fills the Hall, and its graphic wave fills the screen, a portent of CHD – Coronary Heart Disease. Against this pulse, performers press sweets on the audience, muttering fragments of old music hall songs – “when my sugar walks down the street…”, “I’ll be your sweetheart…”, “a little of what you fancy does you good…”. A ghost of Wilton’s past – an old music hall comedian – appears, hymning a lifestyle promoted by the junk food industry. The heartbeat on the screen begins to stutter, the band becomes ragged and the pulse erratic – “a little … of what you fancy … does you … in”.

Three dramatic stories now follow, vividly brought to life in a series of flashbacks. This is the experience of people suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

A survivor of the Bangladesh/Pakistan war recalls being hunted down in the mountains “jolche shorbanash / everything is burning”, while a villager fears for the future of her family; in Angola, a Portuguese conscript soldier wearied of the relentless jungle warfare “as colunas partiam a madrugada / the platoons set off every morning” attempts suicide and is attended by a medical orderly; a refugee from the war in Syria tries to console her child, haunted by the loss of her father and husband.

Their stories are interwoven, and then taken up by four jazz soloists – two trumpets and two saxophones – with the other musicians providing an eloquent instrumental commentary. Overlapping and colliding with increasing frequency, the musical images build to a powerful climax, in which all the singers also give voice: “Horror of war, beyond what words can tell, or a picture-graph…”

The nightmares dissolve into a poignant epilogue – “If music could bind up the silent wound, we would do that; if music could, we would…” Each of the singers ponders on the grudging support society offers survivors of conflict, especially innocent victims, and the limited power of artists to intervene. The audience leaves the Hall and steps back out to Cable Street; they are asked to reflect on what they’ve heard, the need for action, the power of unity and activism, and the positive effects of intervention.

(Phrases in italics are excerpts from some of the lyrics in the show.)

A more detailed version of this scenario, and information about the performers, can be found here on the Grand Union Orchestra website.

Tony Haynes, March 2017